Drama at the Orphanage

From January to April 2012, I did an internship in Romania volunteering in an orphanage and children's hospital. One morning in the orphanage, things were even more out of control than normal. A 2.5-year-old girl named Nadia*, who is confined to a wheelchair due to being born without hips and who's known for notoriously naughty behavior, was pestering another girl, 3.5-year-old Laura*. Laura has almost no control of her body and spends her time in a high chair, with a scarf tied around her and the chair so she doesn't fall out of it.

From January to April 2012, I did an internship in Romania volunteering in an orphanage and children's hospital. One morning in the orphanage, things were even more out of control than normal. A 2.5-year-old girl named Nadia*, who is confined to a wheelchair due to being born without hips and who's known for notoriously naughty behavior, was pestering another girl, 3.5-year-old Laura*. Laura has almost no control of her body and spends her time in a high chair, with a scarf tied around her and the chair so she doesn't fall out of it.

This particular morning, Nadia rolled her chair over to Laura and began untying the scarf. Another intern, Kevin, repeatedly told her to stop, but when no one was looking, Nadia successfully untied it, sending Laura careening to the ground from 4-5 feet up. Laura hit the ground hard and began crying and screaming, the workers were yelling, and Nadia was immediately sent to her crib, bawling because of all the commotion and not understanding why she was at the center of it.

When things settled down, the other interns and I were sitting in the room talking about it. One of the other interns** began to complain about how bad Nadia is and how difficult it is to work with her. Before really even thinking about it, I replied, "It's not her fault." My friend looked at me baffled and retorted, "What do you mean it's not her fault? She was the one that pulled the scarf after Kevin told her over and over again not to. That's why Laura fell!" It was true, but still I replied, "She didn't know that pulling the scarf would make Laura fall. And when I said, 'It's not her fault,' I meant it in a broader sense. It's not her fault that she was born without hips so she's confined to a wheelchair. It's not her fault that she was abandoned and that she's been brought up in a place where it's so difficult to develop social competence. It's not her fault that she's a 'brat.'"

I can't remember what my friend's reaction was, but I remember being

surprised at my own response, especially since I had considered Nadia a

terror for so long as well. But sometime in the course of those few

months (and gradually in the last few years), I had discovered something crucial which changed the way I saw Nadia and the world: one, that I have no good reason not to love her, and two, that I was able and obligated to help her.

*Names have been changed for the sake of privacy

**Who I harbor no ill feelings toward for this or anything elseWho Untied the Scarf?

To make this concept more applicable, consider human nature for a minute: when we see a crime, we look for a criminal, and most of the time we find one. We see Nadia pull the scarf, so to speak. Once we find the criminal, we pronounce blame and deliver punishment (sending her to her crib), and rightfully so. But here's the interesting thing: behind that criminal is a human being with a history full of aspects we don't see. We don't see Nadia's years in a deprived orphanage with uneducated (albeit well-meaning) workers, we don't see her mother abandoning her, and we don't see her mother struggling to support an impoverished family in the midst of a country torn to pieces by a hellish dictator. All we want to know is who untied the scarf.

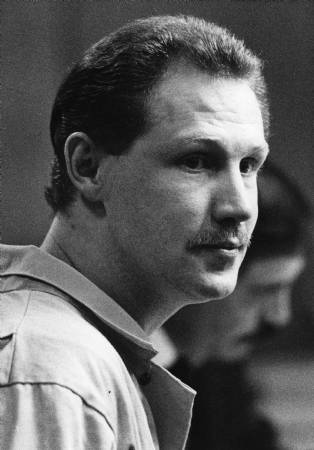

Take a more serious example: we see a man who killed two people. We pronounced blame, delivered punishment, sent him to death row, and probably rightfully so. But how many people saw him "malnourished and wandering the streets alone in a diaper" at the age of 2 because his alcoholic father abandoned him? Or what about when he was sexually abused by his siblings as a child, when he became addicted to drugs and alcohol by age 10, or when he was sold into prostitution by his pedophile foster father as a teenager? Say hello to Ronnie Lee Gardner, one of the many infamous "Nadia"s in the world. And then say goodbye to him, because he was executed in 2010.

|

| Ronnie Lee Gardner |

"What do you mean it's not his fault? He was the one that pulled the trigger after the laws told him over and over again not to. That's why those people are dead!"

But then I see that starving 2-year-old boy, wandering the streets alone in a diaper, and things don't add up quite so easily.

Running in Circles

When I said that I have no good reason not to love Nadia, it applies to Gardner and those similar to him as well. How could I possibly love a murderer? This is best answered using the following fictional yet realistic timeline in which each step is the primary reason for the next:

- Child is born with a difficult temperament.

- Mother finds it too difficult to properly care for the child.

- Child develops an insecure attachment.

- Child begins school and is aggressive and socially incompetent.

- Peers and teacher reject child.

- Child dislikes school and is prevented opportunities to improve social competence.

- Child performs poorly in school and seeks out peers who are similar.

- Child's socially incompetent and antisocial behaviors are reinforced.

- Child engages in delinquent behaviors as a child, adolescent, and adult.

Another interesting thing I found is that the ones who most need our love and attention are those least likely to receive it: the socially awkward, the arrogant, the aggressive, the delinquent, the mentally ill--basically all those who we have a tendency to look down upon or avoid. They're often on a perpetually negative trajectory that will not be changed unless caring and socially competent people like you and I help them change it. But this will only happen when we stop drawing circles and start loving them--stop condemning people and start helping them.

The Blame Game vs. The Change Game

Now, to clarify what I mean by being able and obligated to help Nadia, let's go back to Gardner. After hearing his history and crimes, there arises the question: was his punishment just? Or to ask it in a slightly different way, how much was he really to blame? They're definitely interesting questions, and in my mind, there's two ways to approach this: playing the Blame Game and playing the Change Game.

If you're looking to play the Blame Game, this post has probably made things a whole lot more complicated; suddenly things aren't so clear and you don't know how to divvy out the blame anymore. However, if you're interested in the Change Game, a thousand new avenues just opened up for you to make a positive difference. The rules are simple. The Blame Game ends in blame; the Change Game ends in change. The Blame Game never involves yourself as a player; the Change Game always does.

To play the Blame Game, we would go back and forth and allot various amounts of blame on Gardner himself, the abusers of his youth, his immediate family, their abusers, his extended family, probably society (and politics--there's always politics), and so forth, until we can sit back in our chairs and be satisfied. And why are we satisfied? Because we reached a conclusion that didn't involve us. If there's no blame, there's no guilt, no remorse, and no reason to change, so we can continue to live our comfortable lives in peace.

The problem with those players is that their conclusion is incorrect, because everything involves us. In fact, the whole Blame Game is built on the premise that either (1) we are incapable of controlling outcomes and effecting positive change, or (2) we don't need to, both of which I believe are dangerously false. (Hence my belief that I'm able and obligated to help Nadia.)

The other option we have is the Change Game, which, instead of asking "Who's to blame?" begs the question, "What can I do to change things?" Suddenly you're placed in the middle of all the important players. You go into a profession designed to teach, uplift, or protect people. You vote on legislation to improve the lives of those in your community and country. You're kind to others and go out of your way to make sure people are doing well. You give resources to the physically needy, time and a listening ear to the socially needy, and love and respect to the morally needy. You encourage your friends and your children to do the same.

And as you do these things, something incredible (and incredibly scary) happens. Suddenly Gardner is your student and you could teach him that he's worth something. You're his neighbor and you could report the abuse that's happening next door. You're the stranger on the bus who befriends him and realizes how desperate he needs help, and you could give that to him. And as exciting as that is, it is terrifying. Because unlike the fat cats playing the Blame Game, you're now incredibly vulnerable and potentially accountable. There's guilt, remorse, and every reason to change, and you are forced to choose between a comfortable life and a better world. But how does this game end, if you decide to keep playing? Change in yourself, others, and the world as a whole.

When we see ourselves in the midst of everything, with all sorts of "Nadia"s in our realm of influence, it's obvious that we can at least somewhat control outcomes and create positive change. But what about the second premise, that we're obligated to do so? The truth is, people have questioned this for ages, most notably the one who defensively asked, "Am I my brother's keeper?" Even among those who answer yes to that, reasons vary. One that stands out to me is derived from the mantra "with great power comes great responsibility." If we accept the fact that we have power to improve our world, we must also accept the responsibility to do so. If not for Nadia and Gardner, then at least for their victims. It's really just an extrapolation of the Golden Rule; instead of telling an individual, "I will treat you like I would want to be treated," you're telling the world, "I will make you a better place so that people are treated the way I would want to be treated." And you have the power to do that.

Your Move

I didn't write this post to rant about murderers and Romanian orphans. I did this to take my turn in the Change Game, and now I want you to make your move. I encourage you to embrace your power and responsibility to improve the world, even at the risk of admitting vulnerability and accountability. Resist the urge to play the relaxing yet destructive Blame Game and plunge wholeheartedly into the challenging and adventurous Change Game. And as you and I do these things together, I'm positive that we can actually make a difference. We may never know how many Laura incidents we prevented, how much sadness and anger we eradicated because of our actions. Nor will we fully comprehend the goodness that we helped to foster. But it'll be there. We reap what we sow, and if we sow this change in ourselves, the world will surely reap the benefits.

Brava Liz! Well said and it insights me to change.

ReplyDelete